Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

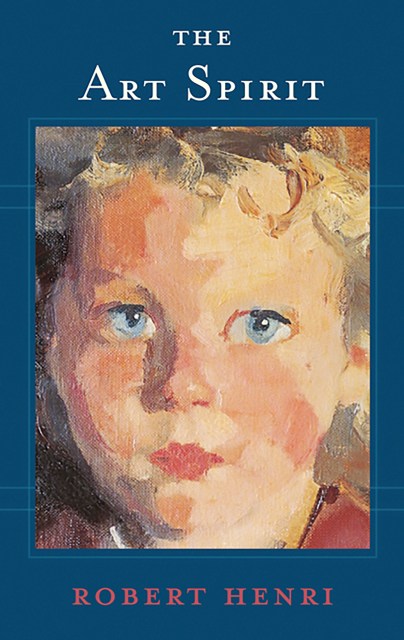

The Art Spirit

Contributors

By Robert Henri

Formats and Prices

Price

$19.99Price

$24.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $19.99 $24.99 CAD

- ebook $13.99 $17.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 27, 2007. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

“Art when really understood is the province of every human being.” So begins The Art Spirit, the collected words, teachings, and wisdom of innovative artist and beloved teacher Robert Henri. Henri, who painted in the Realist style and was a founding member of the Ashcan School, was known for his belief in interactive nature of creativity and inspiration, and the enduring power of art. Since its first publication in 1923, The Art Spirit, has been a source of inspiration for artists and creatives from David Lynch to George Bellows. Filled with valuable technical advice as well as wisdom about the place of art and the artist in American society, this classic work continues to be a must-read for anyone interested in the power of creation and the beauty of art.

Genre:

-

"I would give anything to have come by this book years ago. It is in my opinion comparable only to the notes of Leonardo and Sir Joshua...One of the finest voices which express the philosophy of modern men in painting."George Bellows

- On Sale

- Mar 27, 2007

- Page Count

- 288 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780465002634

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use